‘Building activity extremely slow’: Canada’s housing market was poised for a comeback. Then, trade war jitters set in

Over the past quarter-century, Canada’s housing market has brushed off every crisis that has come its way. It may finally have met its match in the erratic policies of U.S. President Donald Trump.

Sales have plummeted in recent months, pulling prices down with them, while the stock of unsold homes – many of them shoebox-sized condo units in Toronto and Vancouver that were popular with investors but did little to meet the needs of families – is piling up.

With consumer confidence at the lowest level on record and the trade war threatening to both increase the rate of inflation and tip Canada into recession, many experts now expect that housing will create significant drag on the economy.

It’s a stark contrast from last fall, when Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem echoed the widespread sense of optimism in the real-estate industry that falling interest rates would “fuel a stronger rebound in housing activity” this year.

“The risk Canada faces now is stagnation, with both elevated inflation and weak economic growth, and that’s something central banks are not well equipped to fight,” said David Doyle, head of economics at Macquarie Group.

“I don’t think it’s a question of whether housing will pivot and become a tailwind. The debate should be over how significant a headwind the housing market will be.”

Whichever party wins the federal election next week, the next government will inherit a real estate sector in dire straits.

Last month, home sales slumped 9.3 per cent to the lowest level since February, 2009, a month that marked the pit of the Great Recession. In Toronto, only 5,011 units changed hands, the lowest number for any March since 1995, according to Toronto Regional Real Estate Board records.

Prices also slid in March for the third straight month, with the Canadian Real Estate Association’s broad-based MLS Home Price Index down 8.5 per cent on an annualized basis so far this year.

Many Canadians who were actively house-hunting in January have since fled the market.

“I have multiple clients who have put their plans to buy on hold,” said Mike Hattim, a mortgage broker in London, Ont., with Dominion Lending Centres.

“It’s the uncertainty about the tariffs more than the tariffs themselves that is impacting people, whether that’s businesses or individuals,” he said. “How can you make a decision when everything is changing from day to day?”

The housing market is fracturing in other ways. While the inventory of unsold homes is building – for instance, the number of active listings in Ontario is at a 10-year high – builders themselves are putting down their tools.

Homebuilding activity “is extremely slow right now, we’ve had a depressed market for almost two years,” said Larry Masseo, a planner and president of the Waterloo Region Home Builders’ Association.

In addition to the uncertainty around trade and the economy, Mr. Masseo points to a barrage of lingering forces that have buffeted the sector, including slow municipal approvals, rising development charges and higher costs for building materials and labour.

“The tariffs are simply adding a new level of uncertainty on top of that,” he said.

Across Ontario, new housing starts fell to 39,000 on an annualized basis in March, a level not seen since the depths of the Great Recession in 2009, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. reported last week. The sharp slowdown was made worse by inclement weather, but starts in the province have been falling since November.

The slowdown in new home construction is expected to compound Canada’s affordability crisis, as a shortage of new supply could help keep house prices higher for longer.

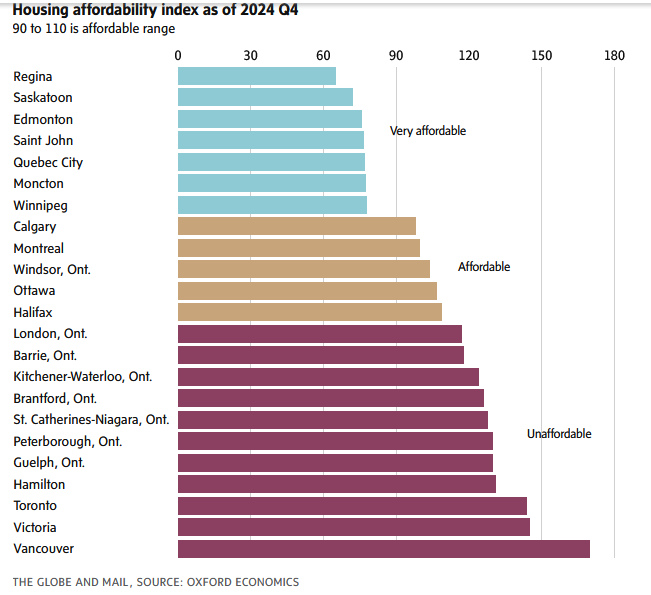

Of the least affordable markets in the country, all but Vancouver and Victoria are in Ontario, mostly in the province’s southern region, according to Oxford Economics’ housing affordability index.

The index is calculated using median household incomes and assumes a down payment of 20 per cent, a gross debt service ratio of 39 per cent, five-year mortgage rates and an amortization period of 25 years.

All of this comes as Canada’s economy could use any boost it can get.

The growth outlook for the country was already uncertain after Ottawa clamped down on temporary immigration by restricting study and work visas after several years of historic population increase. Slower growth is easing pressure on Canada’s rental market – in March, the asking rent for new rentals fell by 2.8 per cent from the same month last year, the sixth straight month rents decreased on an annual basis, according to Rentals.ca. But it also means fewer consumers for businesses.

That was before Mr. Trump launched his trade war and began to demand manufacturers move their operations to the United States. A trade war-induced recession in Canada will lead to around 200,000 job losses by early 2026, according to a new report from by Tony Stillo, director of economics for Canada at Oxford Economics.

Canadian policy makers have been able to count on the real estate sector to revive growth in times of crisis, with falling interest rates spurring home construction, juicing prices and enabling homeowners to borrow against their home equity to splurge on goods and services.

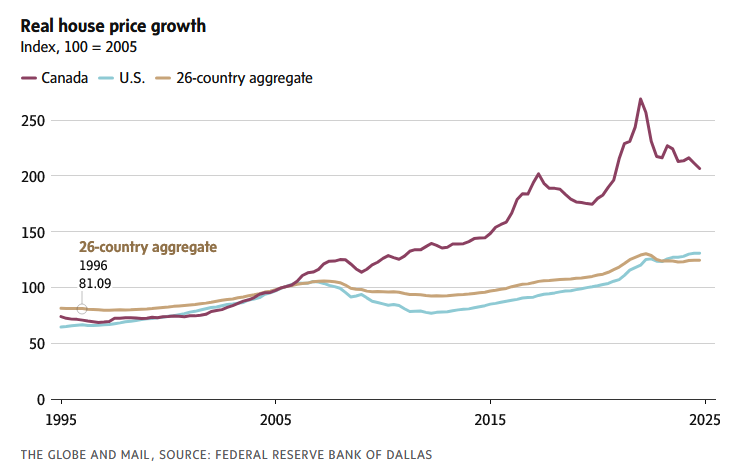

During the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009, in which U.S. home prices plunged an average of 30 per cent and took 14 years to fully recover, Canadian property prices dipped 9 per cent but made that back within a year of the recession’s end. The collapse in oil prices in 2014 caused Calgary’s housing market to stall for five years, but nationally prices soared at double-digit annual rates. Likewise, the pandemic shutdown in March, 2020, briefly brought real estate activity to a halt before it spiked sharply over the next two years.

“The starting point for housing is tougher this time, because valuations got so stretched the last few years,” said Robert Kavcic, a senior economist at Bank of Montreal. Even though house prices since their peak in 2022 have already corrected 10 per cent to 20 per cent, depending on the market, “affordability is still stretched,” he said.

That’s not to say the Bank of Canada is done cutting rates, Mr. Doyle said, but the bank doesn’t have the room for dramatic cuts like it did during the financial crisis because of the risk of tariff-induced inflation.

“Housing won’t become a channel for ignition like it has in the past,” he said.

The Bank of Canada, after seven consecutive interest-rate cuts, put its campaign of monetary easing on hold this month and left the benchmark policy rate unchanged at 2.75 per cent, citing concerns about rising prices.

“The Bank of Canada doesn’t want to get behind the curve and have a repeat of what happened postpandemic so they’re fixated on inflation,” Mr. Stillo said. “They don’t want to be burned twice.”

At the same time, fears of inflation and uncertainty brought on by Mr. Trump’s efforts to tear up the global trading system have been putting upward pressure on bond yields, which underpin fixed-rate mortgages.

“It feels like the best case for housing is five or 10 years where price growth tracks sideways and you get the relief coming through income growth,” Mr. Doyle said.

“But the risk is things spiral with this trade war and we’re into a stagnation environment where it’s not a sideways movement any more, it’s a sharp downturn.”

This article was first reported by The Globe and Mail