‘Eat the tariffs’: More businesses evaluate tariff surcharges as trade wars drag on

With the costs from U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs piling up, companies are doing exactly what economists always predicted they would: Pass some of the pain on to their customers.

That’s putting corporate America on a collision course with the White House. After Walmart Inc. warned it would have to increase prices this month owing to high tariffs, Mr. Trump lashed out last weekend at the retail giant, demanding it “eat the tariffs” instead of raising prices.

But an analysis of corporate calls with investors and analysts using data service AlphaSense shows Walmart isn’t alone in looking for ways to share the burden.

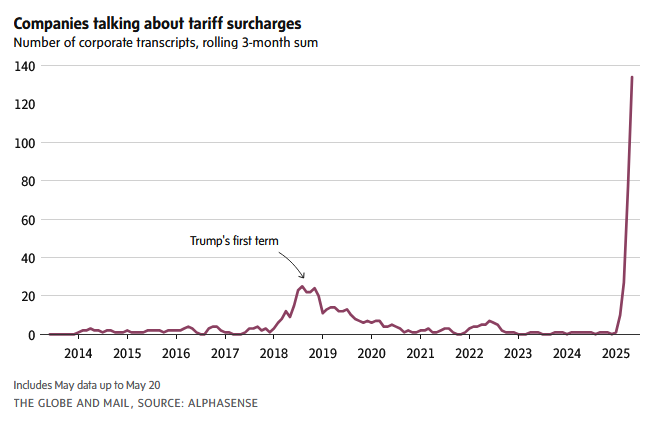

The number of global public company calls mentioning tariff surcharges has skyrocketed since Mr. Trump’s so-called “Liberation Day” on April 2, with U.S. companies accounting for roughly two-thirds of all those discussing the surcharges.

Mr. Trump has long insisted other countries would pick up the cost for tariffs on imports into the United States, despite decades of evidence that tariffs lead to higher prices for domestic consumers.

So far U.S. consumer inflation has remained relatively tame, with prices rising 2.3 per cent on an annual basis in April. Even so, economists are bracing for prices to rise as businesses deplete their stockpiles of pre-tariff inventories and run out of other ways to dodge tariffs.

For instance, International Flavors & Fragrances Inc., a S&P 500 company that manufactures flavours and scents used in food, cosmetics and household products, has altered its supply chain to minimize tariff costs. However, “in select cases where cost impacts are unavoidable, we are implementing targeted pricing surcharges to recover incremental costs,” said chief financial officer Michael DeVeau in a call with investors earlier this month.

As for Walmart, the company released a statement after coming under attack from Mr. Trump: “We’ll keep prices as low as we can for as long as we can given the reality of small retail margins.”

This article was first reported by The Globe and Mail