‘It’s a huge part of our economy’: Canadian government should allow decline in home prices to make housing more affordable, experts say

Housing experts are pushing back against a federal cabinet minister’s recent claim that home prices don’t need to go down in order to restore housing affordability.

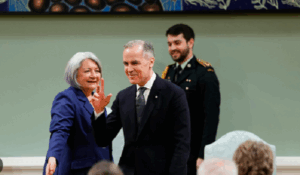

Gregor Robertson, the former mayor of Vancouver who was elected to the House of Commons in April, sparked the debate after he was sworn in as housing minister earlier this, when a reporter asked him whether he thinks home prices need to fall.

“No, I think that we need to deliver more supply, make sure the market is stable. It’s a huge part of our economy,” he said.

Robertson added that Canada lacks affordable housing and championed Ottawa’s efforts to build out the supply of homes priced below market rates.

Mike Moffatt, founding director of the Missing Middle Institute, had a different answer when asked whether housing can be made more affordable for the average Canadian without a drop in market values.

“The short answer is no. It’s simply not possible to restore broad-based affordability to the middle class without prices going down,” he said.

Moffatt crunched the numbers last month on how long it would take for housing to return to 2005 levels of affordability if the average home price holds steady while wages grow at a nominal pace of three per cent annually.

Across Canada, he said, it would take 18 years to return to more affordable home price-to-income ratios — while in Ontario and British Columbia it would take roughly 25 years.

In B.C. and Ontario, Moffatt said, wages and home prices have become so detached from one another that it’s not “realistic” to rely on wage growth to catch up to housing costs.

While Moffatt said he welcomes policies that encourage more housing for vulnerable Canadians and those experiencing homelessness, efforts to build more below-market housing units won’t address the “middle-class housing crisis.”

Days after Robertson weighed in, Prime Minister Mark Carney was asked the same question. Rather than offering a yes-or-no answer, he asserted instead that he wants “home prices to be more affordable for Canadians.”

He cited Liberal election campaign pledges to drop the GST on new homes and offer incentives to municipalities to cut development charges in half.

The Liberals are looking to lower the cost of homebuilding with the aim of doubling the pace of housing starts in Canada. The government wants to scale up the use of prefabricated parts and other technological advances to streamline housing development.

Carney said that this boost in supply would “make home prices much lower than they otherwise would be.”

Moffatt said he agrees that lowering the cost of homebuilding would help to make homes more affordable.

In fact, he said, if the cost of building doesn’t go down and if home prices stagnate or decline, development will immediately cease to be profitable for builders, causing housing starts to dry up.

“I think that should be the primary focus of all three orders of government … figuring out how we can reduce the cost of home construction in order to create affordability and to lower prices,” he said.

Concordia University economist Moshe Lander agrees with Moffatt that home prices must come down if the government hopes to see broad affordability restored to the market over the next generation.

But he also questions whether the federal government should be the arbiter of housing affordability in the first place, given that so many of the political decisions are out of its control.

Lifting regulatory barriers to boosting supply is largely a matter for provincial and municipal governments, as are efforts to encourage more students to develop skills in the trades.

“And so for the federal government to say, ‘We’re going to try and incentivize this,’ I think they’re going miss the mark in whatever they’re trying to do because really, at the end of the day, it’s not their issue,” Lander said.

Lander said he also understands why politicians of all stripes are reluctant to come out in favour of lowering home prices.

Any explicit government effort to bring down housing prices down would be seen as an attack on homeowners’ equity — an asset many use to fund retirements or other long-term savings as they pay off their mortgages.

“Homeowners will not accept it,” Lander said. “And you risk alienating a very sizable and influential voting bloc.”

At the local level, he said, politicians tend to seek the support of homeowners because — unlike renters — they tend to stay put in a riding or district.

Lander said that most efforts to win renters’ votes tend to be “tepid” at best and “counterproductive” at worst. Policies that target the demand-side of the equation — helping Canadians become homeowners — tend to put upward pressure on home prices at the same time, he said.

Lander said part of the path to affordable housing has to be a shift away from the narrative that Canadians have been fed for generations — that home ownership is a lofty goal to aspire to and renters are “second-class citizens.”

“I don’t think that we’re being clear with society that this is what that might look like,” he said.

This article was first reported by The Canadian Press

Craig Lord, The Canadian Press